Behind the Scenes with Memphis Allies: Christina Gann, a guiding light

When the Memphis Allies initiative to reduce gun violence launched in 2021, the enormity of the challenge was understood:

People on the front lines would be working with a high-risk population, but that population wouldn’t just be a collection of clones. Rather, each would have their own story.

True, there were similarities: Many had a weapons charge in their past. Many have been the victim, or intended victim, of a shooting. Many have a relative, or are a friend of someone, who had been shot and thus are at risk for an act of retaliation.

Yet each of these young people is an individual. Each has taken a unique path to the place they are now – participating in the Memphis Allies SWITCH program (Support With Intention to Create Hope).

“When our participants (generally, ages 17-35) start doing really well, start making traction, they’re tired of being in the streets,” says Christina Gann, a licensed program expert for Memphis Allies, who oversees the work of outreach specialists, life coaches, case managers and clinical therapists.

“They start making progress,” Gann continues, “and then they get sucked back in.”

Which can be trying for those professionals working directly with them.

“Last week I explained to the team, ‘They’re going to have a relapse,’” Gann says. “It’s hard when you see someone doing really well, and then they’re friends are calling to them, ‘Come and help me, do this, do that.’”

“But people are working through the stages of change.”

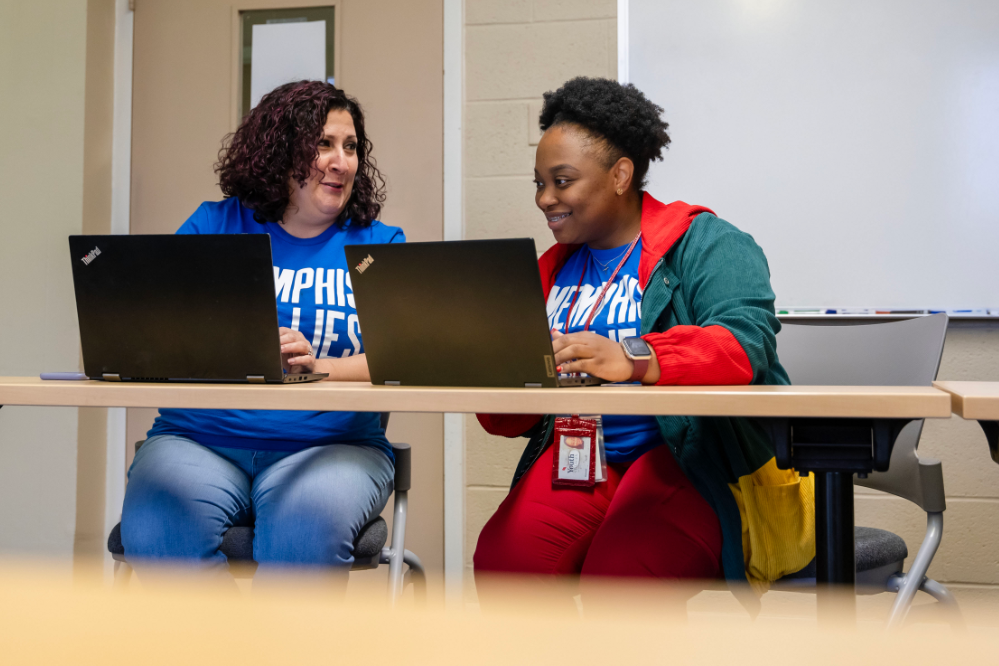

Gann conducts weekly meetings to both monitor progress and the inevitable setbacks that might require adjusting approach.

Diamond Fairley, a clinical therapist with Memphis Allies, appreciates Gann’s guidance.

“She has taught me how to tailor each plan for each participant,” Fairley says.

Gann has more than a decade of experience in the social work field, and it shows when she leads a meeting with life coaches and clinical therapists. Typically, 10 to 15 participants might be discussed in such a meeting, and each has their own narrative.

If they’re really, really high-risk, we’re not letting any of them go if we can help it

– Christina

So, too, the life coaches and therapists have their own ways of working. Some, Gann says, naturally tend to push a little harder. Others might extend grace to the point of suffering “compassion fatigue.” Her job is to keep them centered and, most importantly, to help them understand what’s going on in the participant’s life at that moment.

“Everyone is very passionate about the participants,” Gann says, “so trying to see the big picture can sometimes be challenging.”

And this is where Gann’s experience and insights are invaluable.

“Most of the time she listens and waits for us to ask her to chime in,” says Fairley.

For instance, Fairley had a participant, “Justin,” with whom she wanted to use the “cognitive triangle” – meaning, focusing on thoughts, feelings, and actions. But Gann suggested first uncovering what Justin’s source of stress was. As Fairley explored that, she discovered that in his large family, Justin’s siblings were favored because he was often getting into trouble.

Although he has had some health issues, Fairley says Justin is now avoiding conflict in the streets. Gann’s advice gave Fairley a way to help Justin identify what might stir him up and lead to making bad decisions and acting out, such as stealing cars and carrying a gun.

Gann also has to make the call on whether to move on from participants who are not making progress.

“If they’re really, really high-risk, we’re not letting any of them go if we can help it,” she says. “If they’re not willing to engage with us, we might move them back to the prospect stage and have a specialist reach back out to them. But we don’t give up on them.”

Intervention, of course, is Memphis Allies’ core mission. Gann has witnessed it in action. One recent situation: Someone owed money to program participant “Damian.” And Damian let it be known he was looking for the guy.

“With the intention of shooting him when he saw him,” Gann says. “Staff was able to talk through that with him. If they cross paths, they’re probably going to have words, but he was able to get to a point where he no longer wants to shoot this person.”

And that’s a victory. One less shooting.

In fact, given that on average one shooting in Memphis leads to four more, maybe five fewer shootings.

“What we’re doing is hopefully going to prevent us from needing as many jail beds as we need now,” Gann says. “Also, a lot of our participants are dads. And they want to be good dads. This gives us an opportunity to help them change their mindset and raise their children differently.

“I’m hoping, big picture, we’re breaking some cycles.”

More Posts

Pain is Universal

Image above: Jennifer Davis, Memphis Allies SWITCH program clinical supervisor Memphis Allies Clinical Supervisor Jennifer Davis: ‘Pain is universal.’ Fight. Flight. Freeze. Imagine living every day within one — or all — of those three realms. Many Memphis Allies...

Memphis Allies sees progress in reforming violent offenders. Here’s how

Image above: Memphis Allies Managing Director of Operations Carl Davis and Executive Director Susan Deason pose for a portrait in the recreation area of the facility in Memphis, Tenn., on September 3, 2025. Chris Day/The Commercial Appeal Lucas Finton, Memphis...

Holiday Toy Drive

Image above: Memphis Allies teams up with 103.5 WRBO at the holiday toy drive Community generosity thrives at Memphis Allies toy drive Memphis Allies hosted a Holiday Heroes toy drive in December. Memphis Allies staff, along with radio station 103.5 WRBO, accepted...